Natural Sciences

As a member of the academies of Leuven, Munich, Rovereto and Halle an der Saale, Dominikus Beck, Professor for Mathematics and Experimental Physics in Salzburg, was held in high esteem.

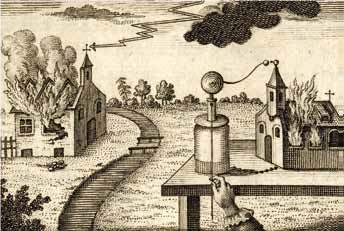

Title page from Dominikus Beck, „Kurzer Entwurf der Lehre von der Elektricität“, 1787 (UBS, Sign. 2764 I)

Dominikus Beck

He had Salzburg’s first lightning rod installed on Mirabell Castle, and was frequently commissioned by the archbishop “to build or improve water edifices and machines.” During a visit to St. Peter’s abbot, he collapsed with the words: ”I’m having a stroke!” Smelling salts, bloodletting, enemas – everything was in vain. The professor died “without recovering his senses.” The abbot had a wax bust of the scholar made for the university’s Museum Mathematicum. However, the jealous colleagues refused to “put” his bust portrait “in the museum,” saying: “If a monument is erected for this man, what will be left for commemorating others?”

A look into the stars

Astronomy and astrology were closely interwoven in the 17th century. Archbishop Wolf Dietrich attempted to manipulate the Emperor’s policy with the aid of a horoscope forged by Tycho Brahe, the court astronomer. Half a century later, the university professor Philibert Utz still cast horoscopes on demand. He also searched for the philosopher’s stone, encouraged by the abbot of his native monastery of Melk: “I do not ask for gold, I shall be satisfied with the silver money that is created.” However, Utz “merely” discovered prescriptions for producing ink, paints and medicine.

— Draco constellation from the Firmamentum Firmianum by Corbinian Thomas, 1730 (UBS, Sign.)

Corbian Thomas

In 1730 the Benedictine professor Corbinian Thomas succeeded with his Firmamentum Firmianum. He used 83 copperplates in colour to present the celestial globe in honour of Archbishop Firmian. The much-liked professor frequently forgot to bring his speech notes – “and yet he always knew how to bring his lecture to a successful conclusion before the eyes of an appreciative audience.”

Flying high

Under great public attention, the young Benedictine Ulrich Schiegg from Ottobeuren mounted the first German hot-air balloon at the beginning of 1784, only three months after the Montgolfier Brothers had done so.

Being called to the University of Salzburg, he taught mathematics, physics, astronomy and agronomy. He provided “the best evidence of the practical value” of his lectures by presenting a wood-saving system for brewing pans, laundry cauldrons and salt production. In 1800 Schiegg took part in the first ascent of the Großglockner, measuring its height and the boiling point of water at the Hohenwart-wind gap (3.281 m), which is 92° Celsius. After the closure of his monastery, he was entrusted with the surveying of the Bavarian provinces in Franconia. When baulking horses overturned his coach, he was nearly crushed by his case of instruments. These serious injuries led to his early death in 1810.

Text: Christoph Brandhuber | Translations: Diana McCoy, Leonie Young

Photos: © PLUS, Universitätsbibliothek Salzburg (1, 2)