Science & Arts

Only a few years after its foundation (1622), the Benedictine University was instrumental in representing regional culture. The professors acted as advisers to the local ruler, drafted Latin inscriptions for the grandest monuments in town, and designed iconographic programmes for churches, palaces and triumphal gates. Even plans for the Residence Fountain were arranged with the university: the remarkable copperplate engraving for a philosophical thesis disputed at the Benedictine University shows the Residence Fountain as early as 1658, although it was not completed until 1661.

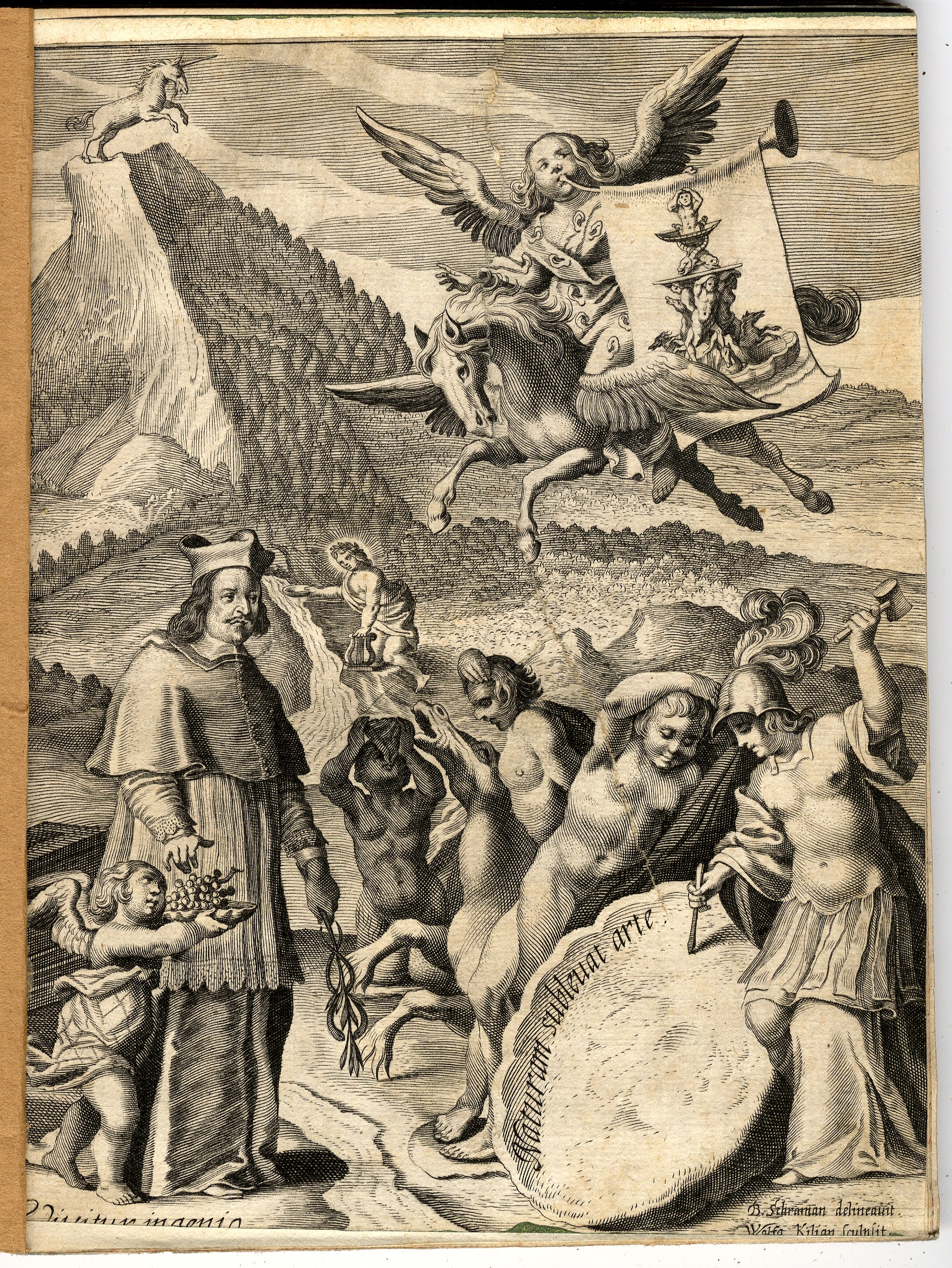

Frontispiece for the thesis “Rivi logici ex fonte Aristotelico deducti”, 1658 (UBS, Sign. R 4448 I)

Construction of the Residence Fountain

Allegory of the Residence Fountain’s construction by Archbishop Guidobald Count Thun: Fama announces the glory of the Residence Fountain, Minerva sculpts the fountain bowl, a unicorn, the archbishop’s heraldic charge, unleashes – in reference to Pegasus and Hippocrene – a spring of water supposed to bring forth poetic inspiration from the Untersberg. The god Apollo is pictured collecting water from this spring. The archbishop carries the caduceus, the staff of Mercury, which guarantees the salus publica, the “public welfare”.

Money makes the thesis bound

An important academic exercise was the disputation, in which a single candidate or a group publicly defended scientific theses. Those who could afford it, or had a rich benefactor, had their theses printed, and distributed to the high-ranking listeners, friends and acquaintances. Individual sheets, elaborately designed, or writings of several pages were published in an edition of 100 through 300 copies.

The imagery of the magnificent copper engravings was usually sophisticated, requiring some knowledge of allegory and emblematics to understand it – skills that were imparted at the university in those days. The thesis sheets also provide insight into former teaching practices. The students delighted in choosing topics of genealogy and history; besides, they preferred employing religious imagery. The engravings were frequently produced in Augsburg, which was the hub of this art form in Southern Germany.

Text: Christoph Brandhuber | Translations: Diana McCoy, Leonie Young

Photo: © PLUS, Universitätsbibliothek