The Court Library

Avid book collectors among the Salzburg Prince-Archbishops amassed an extensive library over the centuries. The Archbishops Pilgrim II von Puchheim, Bernhard von Rohr, Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg and Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau had particularly impressive collections. Maximilian Gandolph Count Kuenburg was the greatest book-lover among Salzburg’s archbishops. When his collection was bursting at the seams, he had a double-span pillared hall built in the New Residence to house 20,000 books. The Court Library was named after him.

“As an everlasting monument to his academic affinity, he left behind a library he had built himself, which was well-stocked with books of every science.”

Historia Salisburgensis, 1692

Max Gandolph Library, Kapitelgasse 5–7

Max Gandolph Library

The archbishop collected pretty much everything that the European book market had to offer. Whitewashed in a grey-yellowish tone, decorated with gleaming coat-of-arms supralibros, his books are still easy to identify today. His successors steadily extended the collection. Due to the Napoleonic Wars, the secularisation as well as the change of the sovereign, Salzburg lost many art treasures. Precious manuscripts, incunables and fine specimens of books were transferred to Paris, Munich and Vienna. In 1807, the Emperor Franz I gave the remaining stock of the Court Library, which contained many treasures overlooked during transport, as a present to the University.

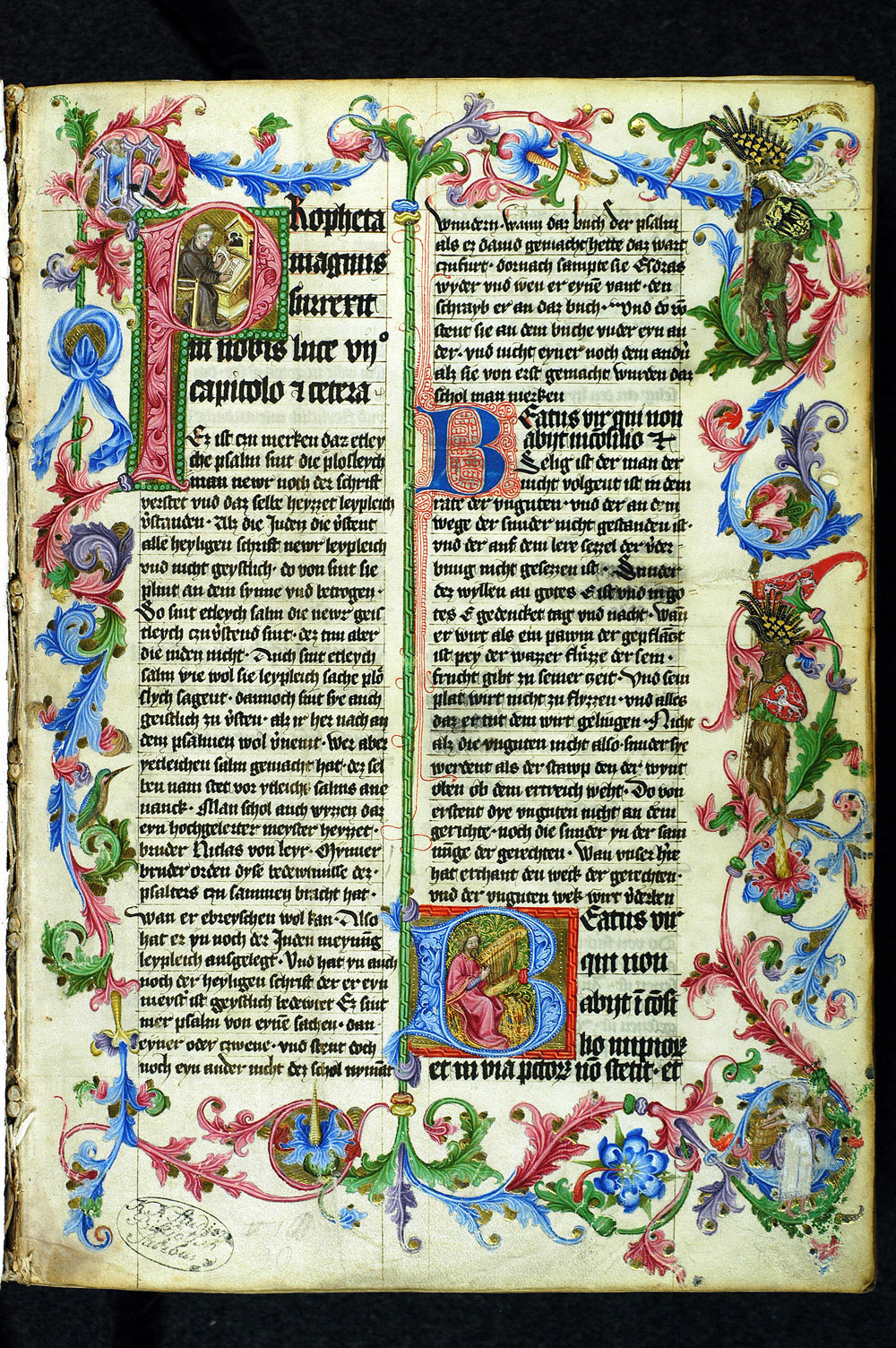

The Wenceslas Psalter, Prague, 1395 (UBS, Sign. M III 20)

The Wenceslas Psalter

One of the most beautiful manuscripts in the University Library Salzburg is the Wenceslas Psalter, a parchment codex executed about 1395. The codex commissioned by the Bohemian King Wenceslaus IV (1361–1419, nicknamed "the Idle"), written and painted in the same Prague workshop as the Wenceslas Bible. One distinctive characteristic of these manuscripts is the use of certain illuminated motifs, which also feature in the Salzburg manuscript: The decorative page on leaf 1r shows us the purple initial W with a prisoner on the upper left, a wild man with helmet, spear and the crests of Silesia and Bohemia respectively in the right margin, a bathing maid with sheep in the lower right, as well as a kingfisher and a love knot in the left margin. This book’s subject matter is rather daring, given that it is a biblical text translated into the vernacular. Emperor Charles IV still confirmed the ban on translating the Vulgate for his domain in 1369. Charles’ son and successor Wenceslas, however, overrode this. The commentary on the Psalms was written in Latin by the Franciscan Nicolaus of Lyra († 1349) and (presumably) translated into German by the so-called "Austrian Bible Translator".

Filippo Buonanni: Gabinetto Armonico. Rome 1722 (UBS, Sign. R 76970 II)

Tromba marina

Filippo Bonanni (1638-1725) was a Jesuit priest, naturalist and microscope maker. From 1698, he curated the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher’s famous collection of curiosities, a typical Baroque treasure trove and forerunner of the later science museums. Often reviled as a "picture book for big children" or an "iconographically controversial collection" is his "Gabinetto Armomico", published in Rome in 1722, which was designed as a universal encyclopaedia of all musical instruments known at the time. 136 copper plates portray European, Asian, African and American musical instruments, although the descriptions do not provide any explanation of the playing technique or repertoire. Bonanni divides his work into wind, string and percussion instruments, including rarer instruments such as the tromba marina (Trompetengeige, Nonnengeige). In contrast to other common stringed instruments, the approx. 2 m long tromba marina is covered with only one gut string. This instrument produces a buzzing sound with a timbre reminiscent of a trumpet. The trumscheit was often played by nuns, as they were not allowed to play real wind instruments for a long time.

Giorgio Bonelli: Hortus Romanus. Rome 1772–1793 (UBS, Sign.)

The marvel of Peru (Mirabilis jalapa)

This work, published in a small number of copies, is characterised by about 800 coloured engravings. Very few editions are coloured. The drawings were produced by the otherwise unknown Cesare Ubertini and engraved in copper by Maddalena Bouchard. The work is usually attributed to the Italian physician Giorgio Bonelli, but he actually only wrote the short introduction. Liberato and Constantio Sabbati contributed the bulk of the work, and Niccolo Martellio was the editor. A complete copy was auctioned at Christie’s for £78,500 (94,000 euros).

Texts: Christoph Brandhuber, Beatrix Koll | Translation: Diana McCoy, Leonie Young

Fotos: © Hubert Auer (1) | © PLUS, Universitätsbibliothek Salzburg (2-4)